Dr. Deganit Ben Dov

Neutering and castrating are the first operations that humans performed on domestic animals. Already in ancient sources such as in hieroglyphic Egyptian writings and in the Bible we can find items relating to the castration of animals. In the past, operations of neutering and castration of domestic animals were carried out for these primary reasons:

A. Work animals, such as oxen and horses, who were castrated, were calmer and easier to work with.

B. Animals who were raised for food and who were forced fed, grew more quickly after they were castrated.

In our times it is acceptable to neuter and castrate pet animals – primarily dogs and cats. Why? The principal problem with which all who are involved with the welfare of animals are struggling is the over population of pet animals. One female dog or cat reproducing without control, can give birth twice a year. Within a number of years, she and her descendents will give birth to tens of thousands of puppies or kittens.

The consciousness of the many advantages of raising pets has risen from year to year. In spite of this, the number of homes and families who are willing to adopt a dog or cat does not approach the number of animals needing adoption. Without control on the reproduction of pets, the organizations for the welfare of animals in the world will be forced to continue to kill millions of cats and dogs each year. The neutering and castration of these animals is the most efficient way to reduce the number of animals that die from lack of a home and care.

Today almost everyone is conscious of the importance of neutering and castration. Besides the reduction of overpopulation, these operations improve the health of pets and lengthen their lives, and of course makes life easier for the owners who don’t have to deal with the problems of heat and finding or not being able to find home for the puppies or kittens.

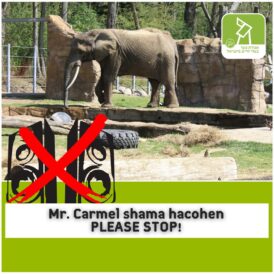

Most of the societies for the welfare of animals insist on the neutering of animals that are given for adoption. There are societies where these operations are done on the premises and there are those that refer the adopters to neutering facilities in various veterinary clinics. In the United States, in societies that give out animals for adoption and have the adopters sign a statement of obligation to have the animals neutered, there is a follow up that discovered that a third of the owners do not return to have the operation performed. One female dog or cat, that has not been neutered, can give birth within a number of years to enough young to fill up the pounds.

More and more charities are changing over to a policy of neutering and castration of each animal before it is given to new families. Only those societies for animal welfare who maintain a policy of neutering and castration of every animal before it is given for adoption can be certain that the animal will not contribute to the over-population of pets.

When should it be done? There are those who think that it is preferable for the female dog or cat to give birth once before it is neutered. This was the acceptable opinion until a few decades ago. Later it was found that neutering before puberty contributes to the health of animals who are operated upon and extends their lives, and the age that is recommended for the operation was near to the age of puberty, or between 6 to 8 months. In many cases puberty is earlier, especially in kittens who can become pregnant a the age of 4 months. This problem brought about the fact that in the nineteen eighties, operations of neutering and castration were carried out already at the age of 6 to 8 weeks.

Various veterinarians brought up the fear of the long term influence of neutering at a young age. This fear lead to the many research projects that examined tens of thousands of dogs and cats that were operated on at a young age. These researches reinforced the information about the contribution of neutering and castration before puberty to the health of the animals and showed that there were no differences between neutering at 6 to 8 months and neutering at the age of 6 to 8 weeks. An additional finding related to the operation itself. Neutering of the younger ones is easier for the surgeon, and more important than that, for the young one itself—the operation is shorter and the recuperation is very much quicker. About an hour after the end of the operation on a female kitten of 8 weeks, it is already eating and playing.

Who? The results of these research projects brought about that in 1991 societies for the welfare of animals and various veterinary organizations were recommending neutering and castration at a young age. In places where they instituted neutering at a young age, the number of dogs and cats put to death was lower. Neutering at a young age, before puberty, gives the organizations for the welfare of animals a significant advantage in the possibility of neutering before giving the animal for adoption and reduces the need for dealing with over-population of pets. The reduction in reproduction saves lives and resources. There are those who suggest including neutering in the treatment of the puppy or kitten with the inoculations before puberty. This procedure would prevent unwanted pregnancies and would reduce the possibility of cancer of the mammary glands or prostate diseases in the future.

To date, many societies have adopted the technique of early neutering and castration, with all its advantages: The American Veterinary Association, the Canadian Veterinary Association, the American Humane Society, the Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in Israel, etc. The principal objectors to this technique are those who have not tried it. Veterinarians and organizations who experimented with carrying out neutering and castration operations on dogs and cats at an early age prefer to continue with this policy in the merit of the many advantages to the individuals operated upon and to the whole pet population.

This article appeared in the magazine of S.E.P. Pets in July 2001.